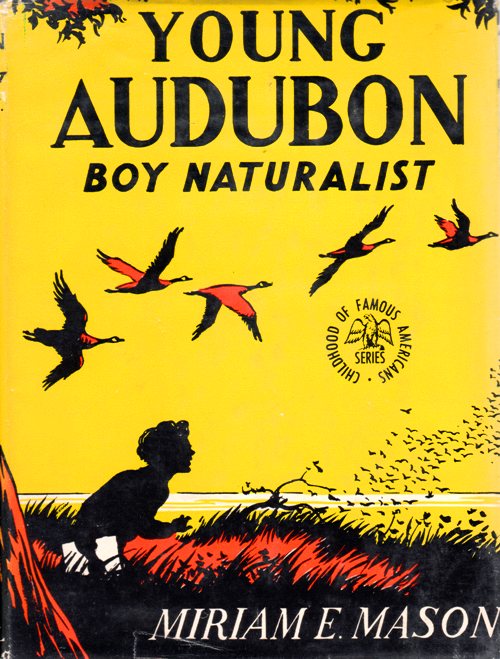

Today I finished reading Young Audubon: Boy Naturalist by Miriam E. Mason.

The book details the early life of John James Audubon and ends with his trip to America and a quick overview of his future there.

The book details the early life of John James Audubon and ends with his trip to America and a quick overview of his future there.

When you see biographical information about Audubon today, you will not see that there is any question about his birth and early years, but at one time there were questions about who he was.

This book was written in 1943 at which time there was less mystery about his childhood and origin.

John James Audubon was the son of Lieutenant Jean Audubon and his mistress Jeanne Rabin and was born in 1785 on his father’s sugar plantation in the Caribbean. He was later taken to France and was legally adopted by his father.

When Constance Rourke wrote Audubon in 1936 there were questions about who he was, and she brings this up in the introductory chapter and also returns to it several times during the book.

When Constance Rourke wrote Audubon in 1936 there were questions about who he was, and she brings this up in the introductory chapter and also returns to it several times during the book.

John James Audubon was always evasive about his origins and would often give conflicting information when asked about his past. He also used several different names throughout his life and this also added to the mystery. Even some of his descendants made claims of a different origin for him than being the son of Jean Audubon.

So, who did people think John James Audubon really was? At one time he was thought to be the lost Dauphin, Louis-Charles, Prince Royal of France.

Audubon never made an outright claim to being the Dauphin, but did make hints that he had an origin other than what was known. It was only after his death that people tried to make the connection.

At one time there were quite a few claims of people being the Dauphin. Remember the Duke and King in the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn? This was not an unknown claim

I will not go into details, but a study of the logic behind the claim for Audubon is very interesting. Today no one would claim that he was the Dauphin, especially after additional information about his early life has been discovered. There was also a well researched article published between the two books above that disproved the Dauphin claim. Plus, modern genetic testing shows that the Dauphin did not survive his captivity as some had claimed.

I had never heard of the claim until I read the book by Rourke, and found it very interesting. I am a big fan of Audubon, and this makes him even more interesting to me. Of course, I don’t think he was the Dauphin, but it is interesting that he was such a mystery.

I have several sets of Audubon prints. They are only from the early 1900’s so are not original, but are still of great interest to me. Especially as they were given to me by the Grandma.

I have several sets of Audubon prints. They are only from the early 1900’s so are not original, but are still of great interest to me. Especially as they were given to me by the Grandma.

I could have used the print above in my post on The Trumpet of the Swan. Instead I used pictures of Trumpeter swans that I had taken at the Toronto Zoo.

I also really like this print of the Blue Jay. This brings back memories of the high school that I went to. Our mascot was the Blue Jay.

I also really like this print of the Blue Jay. This brings back memories of the high school that I went to. Our mascot was the Blue Jay.

I have always liked Audubon prints and after reading the two books above I have a much better appreciation of what he went through to learn how to create them and also to find the subjects of the prints.

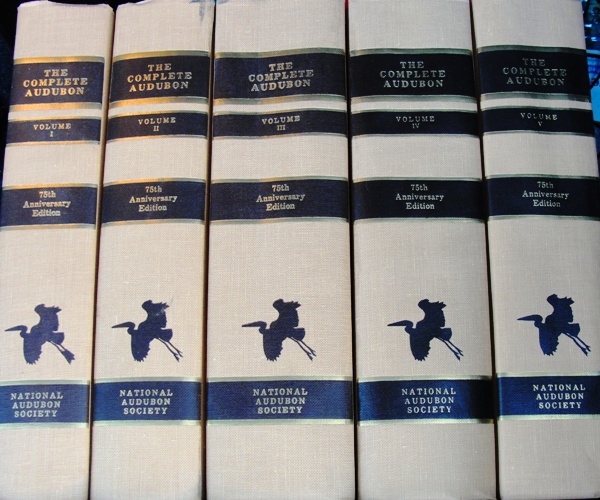

I also have a set of The Complete Audubon that I found at a used book store. I wrote about finding it in my post A Basket Full of Books.

I also have a set of The Complete Audubon that I found at a used book store. I wrote about finding it in my post A Basket Full of Books.

This also makes me think of a cousin who was an ornithologist. Someday I will feature him in a post. He made some great contributions to the field in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s.

What is your favorite bird?

Steven

Good post – I enjoyed reading it. Not sure that I have a favourite bird but it might be the blackbird, there are several who reliably visit my garden every day. Trivia time – it is the national bird of Sweden.

I love the birds that feed at our feeders. We even had a red shouldered hawk and 2 doves today, along with blue jays and cardinals.

Good you found the prints.

I had no idea about the Dauphin controversy involving Audubon – how strange! I remember that Blue Jay print from a bird coloring book I had as a child; I remember being rather aghast at how they were savagely eating those eggs. Looking at it now I’m impressed at the range of Blue Jay moods he depicts: crest raised, feathers sleeked down, and wings open begging. I’d like to know how much time he actually spent watching live birds, since I know he drew from posed dead specimens, but I’d be surprised if he could just make up the range of feather-expressions he shows in the jays from looking at dead specimens alone.

Read the book by Rourke. It details a lot of his travels and the time he spent observing birds. He really wanted to make them look as natural as possible.

Pingback: Research Reading | Braman's Wanderings